Worry Well

SURPRISINGLY, WORRYING SOMETIMES IS HELPFUL…

Most of us worry at least some of the time. We can’t help it. From ‘Will I be late?’ to ‘Did everyone hate the meal I cooked?’ to ‘Am I going to get the sack?’ it’s possible to worry about pretty much anything. And some of us worry more than we are comfortable with and that too we cannot help.

Living a worry-free life is often seen as a desirable—and achievable—goal. But, according to experts, not only is it unreasonable to eradicate all worry, if we did so, we could miss out.

‘We can’t expect to rid ourselves entirely of worry,’ says psychotherapist Andrea Perry. ‘Far better to recognize it as the healthy life force it is. I think it’s important, because if we see anxiety or worry as the enemy, then we want to push it away, stamp it out, get rid of it. But if we see it as telling us something, and we can use it to find ways to take better care of ourselves, that’s far more useful.’

So, how can we better understand our worry, and learn to use it to our advantage? ‘The price we pay for being able to think about the future is to know that we are mortal, and to know we are vulnerable,’ says Dr Martin Rossman, author of The Worry Solution. Our worries are rarely about what is happening right now, in the present moment. If we stop to examine them, we can see that they are about the prospect of some kind of future calamity. What if you are running late? Will your friends be angry with you, disown you, will you be left alone? What if you lose your job? Will you end up penniless and homeless?

‘Worry is often described as an allergy to uncertainty,’ says Dr Kevin Meares, consultant clinical psychologist for the Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust. ‘For a worrier, only small amounts of doubt are required to set off a large amount of worry,’ he says. ‘If you try to live your life by limiting uncertainty, you end up in a difficult place. You become controlled by routine.’

‘I used to feel terribly anxious about going to new places, in case I got lost or turned up late, so I’d make extremely detailed maps and lists of directions, and always leave at least an hour earlier than I needed to,’ says Theresa, 42. ‘Even then, if there were a traffic jam I’d get panicky and stressed, so I started to avoid going to new places altogether. It wasn’t until my partner pointed out how difficult this was for him that I decided to see a counsellor.’

One of the reasons we find it so difficult to worry less (no matter how much our exasperated loved ones may plead with us to let it go or that it doesn’t help) is that it can give us a kind of comfort. ‘There are psychological rewards for worrying, even when we worry about the things we can’t change,’ says Rossman. ‘Worrying about something can partially satisfy a sense that we are controlling or doing something about whatever is worrying us.’ And when your most worrying predictions fail to come true, it’s tempting to think it’s all down to you.

‘The brain may interpret the connection between the worrying and the fact that the event never materialized as evidence we are exerting some kind of control over the situation,’ says Rossman. ‘It’s easy to see how this kind of “successful” worry can lead us to an irrational yet powerful feeling that we can fend off undesirable events.’

The upside of worrying

Although most of us are aware of the problems worry can cause, we may not realize it can have benefits, too. ‘It’s a good way of thinking rapidly about problems and solutions,’ says Meares. Worriers like to be prepared. They will over-rehearse presentations, they will double check everyone has their passport, they will never be without a map or an emergency fund.

For this reason, worriers can be valuable people to have around. ‘The question is, how do you use your anxiety?’ says Perry. ‘Do you use it to make effective choices or does it completely deactivate you? If, for example, it makes you feel you’re not good at your job and you push yourself hard to compensate, then your employer may get fantastic work from you.’

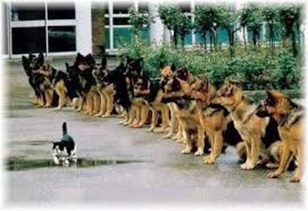

Perry also points out that worriers are like ‘canaries in a coal mine’ – they foresee problems that others don’t. While researching her book on claustrophobia, she spoke to many sufferers who felt anxious about taking the Eurostar train from London to Paris. ‘Then, when a train broke down in the tunnel and people were trapped for 12 hours, the authorities said they’d had no way of preparing for something like that to happen,’ she says. ‘Anyone with claustrophobia could have predicted a train breaking down and people being trapped. In some circumstances, we need those people who have taken every care to make sure the worst doesn’t happen.’

This doesn’t mean that your worry, however productive it makes you, feels any less stressful. But taking time to consider the benefits, as well as the ways you can manage your feelings of uncertainty and anxiety better, is an important first step in learning how to worry well. The goal is not to stamp out worrying, it’s about changing the way you react. It is important to learn to begin to move away from the content of the worry and think about the underlying process.

A tool for self-knowledge

And if we can do this, we come to one of the most useful functions of worry—the insights it can give us to our subconscious thoughts. ‘We all worry about the things that are important to us – our aspirations – and our worry improvises around those aspirations,’ says Meares. ‘For example, someone may say they’re worried about being late for a meeting. When that person explores that worry further, they realize that they are worried about appearing indifferent to their commitment. Understanding what goals drive our worry appears to be an important step in overcoming it.

This can also help us evaluate what is important to us.’ In the case of the individual who is worried about being late for the meeting, he discovered that what is important to him the value of his reputation and wanting to be a person of integrity. Meares often uses the cognitive behavioral therapy technique of the downward arrow (look for the Downward Arrow Technique that I’ve also posted in my Reflections page) to help individuals examine their thoughts. “In this way, worry can be an important tool for self-knowledge,” he says.

If you want to get to grips with it, the first step is to determine whether your worry has a real solution. Talking to trusted friends or a professional counsellor could help. But perhaps the most important thing to remember is that there’s a place for worrying in everyone’s life. We can reduce it, but none of us can stamp it out completely. And we may well become a stronger, more capable person if we can learn to use it to our advantage.

If we are going to worry – and let’s face it, we are – we might as well learn to worry well.

For many of us, the most difficult word to say is one of the shortest and easiest in the vocabulary: No. Go ahead, say it aloud: No. “No”… simple to pronounce, hard to say. We’re afraid people won’t like us or we feel guilty. We may believe that a good employee, parent, spouse, child, parent, good friend religious person never says “no.” The problem is, if we don’t learn to say “no,” we stop liking ourselves and the people we always try to please. We may even punish others out of resentment. When do we say “no?” When “no” is what we really believe. When we learn to say “no” we learn to stop lying. People can trust us and we can trust ourselves. All sorts of good things start to happen when we say what we mean. If we’re scared to say no we can buy some time. We can take a break, rehearse the word, and go back and say “no.” We don’t have to offer long explanations for our decisions. When we can say no, we can start to say “yes” to the good. Our “no’s” and our “yes’s” begin to be taken seriously. We can control of ourselves. And we learn a secret: “No” isn’t that hard to say. ( The Language of Letting Go by Melody Beattie)

For many of us, the most difficult word to say is one of the shortest and easiest in the vocabulary: No. Go ahead, say it aloud: No. “No”… simple to pronounce, hard to say. We’re afraid people won’t like us or we feel guilty. We may believe that a good employee, parent, spouse, child, parent, good friend religious person never says “no.” The problem is, if we don’t learn to say “no,” we stop liking ourselves and the people we always try to please. We may even punish others out of resentment. When do we say “no?” When “no” is what we really believe. When we learn to say “no” we learn to stop lying. People can trust us and we can trust ourselves. All sorts of good things start to happen when we say what we mean. If we’re scared to say no we can buy some time. We can take a break, rehearse the word, and go back and say “no.” We don’t have to offer long explanations for our decisions. When we can say no, we can start to say “yes” to the good. Our “no’s” and our “yes’s” begin to be taken seriously. We can control of ourselves. And we learn a secret: “No” isn’t that hard to say. ( The Language of Letting Go by Melody Beattie)

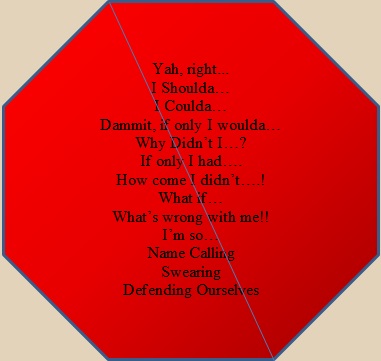

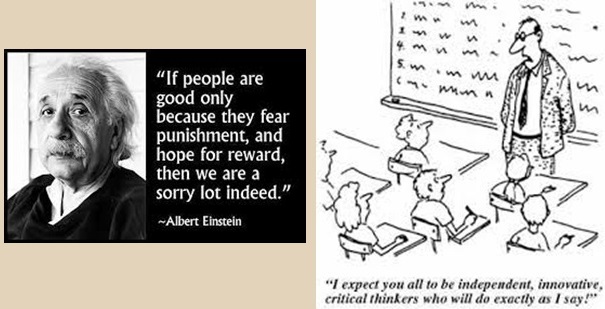

Punishment is a behavior growing out of anger and it can take many, many forms: a loud voice, a sharp tongue, a rough hand, a glaring eye, a silent look, a turned shoulder. The origin of the word “punishment” means “to take vengeance.” It is used against others and all-too-often we use it against ourselves and are left in the wake of the effects of its destructive shaming and guilt. It is designed solely to reduce the likelihood of the occurrence of certain behaviors which we do not agree with and want to keep from occurring in the future.

Punishment is a behavior growing out of anger and it can take many, many forms: a loud voice, a sharp tongue, a rough hand, a glaring eye, a silent look, a turned shoulder. The origin of the word “punishment” means “to take vengeance.” It is used against others and all-too-often we use it against ourselves and are left in the wake of the effects of its destructive shaming and guilt. It is designed solely to reduce the likelihood of the occurrence of certain behaviors which we do not agree with and want to keep from occurring in the future.

Discipline, either toward another or toward ourselves, (self-discipline) is the art of making a “disciple” of one’s self. The origin of the word, “disciple” means “to instruct, to teach, to learn.” W. J. Bennett writes, in The Book of Virtues, “One is one’s own teacher, trainer, coach and ‘disciplinarian.’ It is an odd sort of relationship, paradoxical in its own way, and many of us do not handle it very well. There is much unhappiness and personal distress in the world because of failures to control tempers, appetites, passions, and impulses. ‘Oh, if only I had stopped myself’ is an all too familiar refrain”. In our lives, we will continually be in the process of disciplining ourselves by effectively managing our anger, our appetites, our passions, our impulses, then disciplining (teaching) ourselves (and others) by letting ourselves (and others) to experience the natural consequences of choices, the consequences that flow freely from the choices that are made. Self-discipline need not be harsh; it can take the form of a quiet resolve or determination that then directs our choices. It is exacting, but is rarely served by our being self-critical or self-denigrating. Self-discipline allows us to make use of whatever power and capabilities have been given us, to be all that we can in the service of our dreams.

Discipline, either toward another or toward ourselves, (self-discipline) is the art of making a “disciple” of one’s self. The origin of the word, “disciple” means “to instruct, to teach, to learn.” W. J. Bennett writes, in The Book of Virtues, “One is one’s own teacher, trainer, coach and ‘disciplinarian.’ It is an odd sort of relationship, paradoxical in its own way, and many of us do not handle it very well. There is much unhappiness and personal distress in the world because of failures to control tempers, appetites, passions, and impulses. ‘Oh, if only I had stopped myself’ is an all too familiar refrain”. In our lives, we will continually be in the process of disciplining ourselves by effectively managing our anger, our appetites, our passions, our impulses, then disciplining (teaching) ourselves (and others) by letting ourselves (and others) to experience the natural consequences of choices, the consequences that flow freely from the choices that are made. Self-discipline need not be harsh; it can take the form of a quiet resolve or determination that then directs our choices. It is exacting, but is rarely served by our being self-critical or self-denigrating. Self-discipline allows us to make use of whatever power and capabilities have been given us, to be all that we can in the service of our dreams.